Promiscuous Oaxacan Pink Tomato

(Or, How we started a tomato breeding project, accidentally)

Before we ever set up a tent at a farmer’s market, in 2022, we gave ourselves just one season to test the potential of dry farming on our hillside. Copious amounts of dairy manure, specialized attention to a very small plot, a close windscreen, late summer rains, and a lack of extreme temperatures meant squash and even kale performed well without irrigation. Wryly, we call this year “the trick.”

We grew only a few tomato varieties, the reliably productive Matt’s Wild Cherry, Cherokee Purple, Blueberry, and Oaxacan Pink. Matt’s Wild Cherry remained productive, almost 100% of the Cherokee Purple fruit suffered from blossom end rot, and the Blueberry was inedible. Oaxacan Pink however, produced large amounts of ribbed fruits in varying sizes, and the flavor had a depth and quality we hadn’t experienced before.

Looking back, we can’t really explain what possessed us when we ordered Oaxacan Pink seeds from Siskiyou Seeds. The photo is not promising of anything like marketable fruit. We can only say that our previous experience with the productivity and intense flavor of Matt’s Wild Cherry led us to believe that varieties closer to the heart of tomato domestication held more flavor and would perform better in wilder, more extreme environments.

Siskiyou Seeds’ Oaxacan Pink Tomato:

2022 Test Year: Variable-Sized Fruit & Variable Ribbing

Most of our Oaxacan Pink fruit was ribbed and blocky, as wide as it was tall, but some larger fruit resembled the curved kidney shape of the traditional Jitomate Riñón found in Oaxaca, albeit much smaller. Our fruit averaged just an ounce, which we have had a lot of anxiety about until recently reading Yvonne Socolar’s articles (linked on our Dry Farming page), which indicate that the hailed dry-farmed Early Girl tomato in Coastal California is, in fact, generally that small.

Surprisingly one plant produced consistently oblong shaped fruit, generally with a single rib (like a peach or a plum), in the same rose-hued red of the ribbed fruit and usually with a dimpled bottom. What was it? A mistaken seed in our packet? Something hybridized with Oaxacan Pink? We have reached out to Siskiyou Seeds a few times to ask for their best guess but never heard back.

Back in 2022, listings for Oaxacan Pink seeds were rare. Through a reverse image search of the unappetizing photo, we found an Italian seed seller using the following description: “Oaxacan Tomato (Lycopersicon lycopersicum): From the state of Oaxaca in Mexico, a hotbed of biodiversity and heirloom varieties, comes this pink tomato with a unique flavor reminiscent of the first selections of this species. The berry is small, weighing 150 to 200 grams, flat on the bottom and heavily ribbed. The skin is very thin, the flesh juicy, slightly acidic, and has an exotic, untamed flavor. The indeterminate and particularly vigorous plant is productive and tolerates heat well; excessive pruning is not recommended: the best fruits are found sheltered among the dense foliage. Suitable for particularly dry climates, it is ready in 75 days from transplanting.”

We have since found a much older advertisement (based on the photo quality) on Rich Farm Garden, with a decidedly different looking fruit.

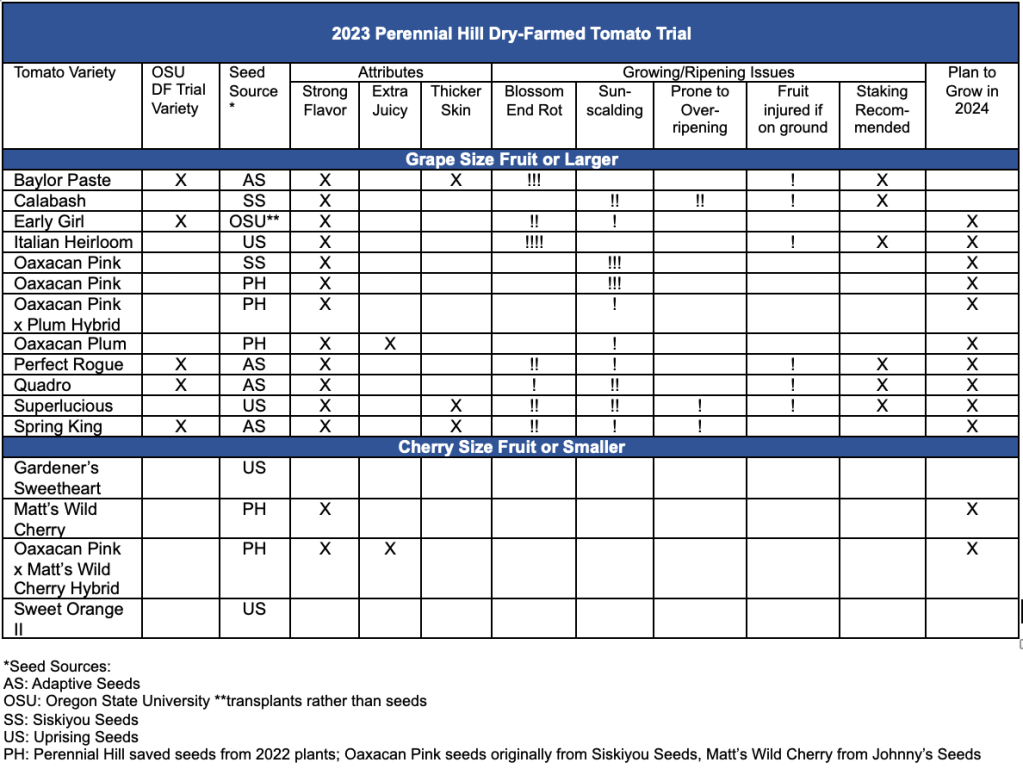

2023 Tomato Variety Trial

In 2023, our first year attempting to grow for market, we had our somewhat indiscriminately saved seeds from both the ribbed and the plum style fruit, which we began calling Mystery Plum. That year the weather was against us. Both in taking on too much scale and buying into the idea that regular levels of fertilization might invite blossom end rot in dry farming, we starved our plants of not only water but nutrients. We grew many, many varieties of tomatoes alongside our saved Oaxacan Pink seeds.

Most of our trialed tomato varieties did not make it to the market. Plagued with blossom end rot and sun scald during triple digit heat, our harvest was pitiable – except from our Oaxacan Pink plants and our Matt’s Wild Cherry. During triple digit heat days pounds and pounds of tomatoes were harvested due to sunscald and sent directly to the compost pile.

From our Oaxacan Pink seeds, we saw plants that produced all ribbed fruit, or all plum style fruit, and then plants that had both. We also had Oaxacan Pink plants that produced cherry fruit. Delicious rose-hued cherry tomatoes. Our only explanation for this is that in our initial trial year, our Oaxacan Pink plants had hybridized with the Matt’s Wild Cherry. Understandable, since the Matt’s Wild Cherry vines escaped their row and often were found intertwined with the Oaxacan Pink plants. While other farmers winced and lamented the promiscuousness of “older varieties,” we were glad to have productive plants with marketable fruit and amazing flavor, which we called “Pink Teresa” in honor of Teresa Arellanos de Mena, the woman who brought Matt’s Wild Cherry to the US from Mexico. Upon buying one box, a customer snacked while walking through the farmer’s market and ended up back at our booth buying several more boxes upon finding out that we wouldn’t be there next week.

2023 Mystery Plum, Oaxacan Pink, and Sunscalded Fruit

Disappointing 2024

In 2024, we attempted to address under fertilization, but shifted our planting method to more closely match OSU & Coastal California’s methods. Planting smaller plants early – at greater scale. This proved to be the wrong way to go. We believe the early summer winds from the north and cold nighttime temperatures stunted the growth of our tomato plants. Vegetative growth was smaller than ever before. Again our Oaxacan Pink, Mystery Plum, Pink Teresa, and Matt’s Wild Cherry made up our marketable tomato harvest despite the handful of other varieties that we had planted. Sunscald again proved an issue on the south face of the fruit during some high temperature days, though much less than 2023. Errant summer rainfall resulted in split fruit. We again grew out new Oaxacan Pink seeds sourced from Siskiyou Seeds, and also newly sourced Oaxacan Pink seeds from Sow True Seed, but neither was productive enough to warrant saving.

Corner-Turning 2025

In 2025, we planted the field mostly with our saved Oaxacan Pink, Pink Teresa, and Matt’s Wild Cherry (Mystery Plum seedlings were devoured by mice in the greenhouse), but we planted them late. Late like we had in 2022. When nervously sharing our planting method plan, a neighbor in the surrounding foothills agreed that May was just too early and too cold to put tomato plants in the ground outside. We still started our seedlings in mid March, transplanted seed blocks into four-inch pots and again into one-gallon nursery pots. Plants were kept pruned to a single leader and any flowers removed. When they finally went into the ground in early June, we planted the gangly plants horizontally, burying the majority of the stem into wet ground. We fertilized each plant with blood meal and bone meal, and watered them in. Then with warnings of extreme heat in mid August, we strung up a shade screen over our Oaxacan Pink plants using leftover material from our field’s deer fence/windscreen.

From our Oaxacan Pink seeds, we planted mostly seeds saved from the blocky, ribbed fruit. The year prior, we had carefully selected fruit for seed saving from productive plants, as well as a smaller section of seeds saved from kidney shaped ribbed fruit. There was noted difference in the production of the plants grown from seed from a kidney-shaped fruit versus plants grown from seed from blocky-shaped fruit. The blocky-shaped fruit seeds produced the variety we have come to expect from Oaxacan Pink: mostly blocky fruit and occasionally kidney-shaped. The fruit on the plants from kidney shaped seeds grew much larger than we have ever seen, but were slow to ripen, prone to cracking while forming, and bursting during rainfall: none made it to market. The shape of fruit resembled that of Zapotec Pleated: ribbed and trapezoid shaped. A few plants had large, rounded fruit, mostly lacking any ribbing. Smaller fruit from these plants that did ripen to marketable fruit was rare but incredibly delicious.

Almost all of our tomato plants were planted horizontally save a few Oaxacan Pink plants, which we planted deeply in a vertical fashion. In the following fall, before planting our cover crop, we dug up a few plants, to see with our eyes what ought to be very obvious: the horizontally planted root ball and stem maximized the surface area in which the tomato plant could send roots down (in the direction of gravity) into the soil. The deep vertical planting indeed grew out roots from the stem, but still only grew roots directly beneath the plant. When we put our plants in the field little more was above ground than if we planted plugs, but the buried stem and root ball – what was below ground – was much larger. When planted, the stem left above ground is initially almost parallel to the surface of the soil, but it only takes an hour or so for them to bend and grow upwards: towards the light and away from the pull of gravity.

Growing out large plants in the greenhouse and planting them horizontally in the field with almost the same level of care provided to a hand-planted, potted tree is incredibly laborious, but then again, we spent no time pruning, staking, watering, or fertilizing after planting. From early June to our first appearance at the farmer’s market in mid-August, the tomato plants received no care save the stringing up of the shade screen and mowing of the paths between the rows.

Several things all came together in 2025: we avoided too cool early soils by delaying planting, we gave the plants maximum opportunity to find soil moisture and nutrients by planting horizontally, we had seeds that had the benefit of having grown successfully under dry farming conditions for three generations at our site, and the all-important shade screen prevented sunscald. The yield still remained much lower than we would like, and harvests were lower in weeks with high temperatures or errant rainfall, but we finally had a decent offering for our market stand.

Land Race Tomato Variety Origins

Interestingly, in 2025, we have found that listings for Oaxacan Pink seeds have increased exponentially. Some use the unappetizing photo found at Siskiyou Seeds, others show a ribbed trapezoid fruit reminiscent of Zapotec Pleated, and still others depict a ribbed kidney style tomato. Vaguely aware that we had never had our tomato plants spaced far enough apart to prevent cross pollination, and having grown out our Pink Teresa cherry tomatoes for several years, we understood the potential for interbreeding, but it was not until a market goer stopped by our stand and discussed Joseph Lofthouse and his landrace tomato breeding projects, that we fully recognized the open (promiscuous) flower form of our Oaxacan Pink plants and a likely explanation for this extraordinary diversity in fruit, and the surprising divergence in fruit type that we saw in 2025.

Is our Oaxacan Pink genetically the same as the others being sold online, or even of that that Siskiyou Seeds, our initial source, is selling? Probably not. Is there some magic variety out there that matches our plants? Probably not (and yet still we search).

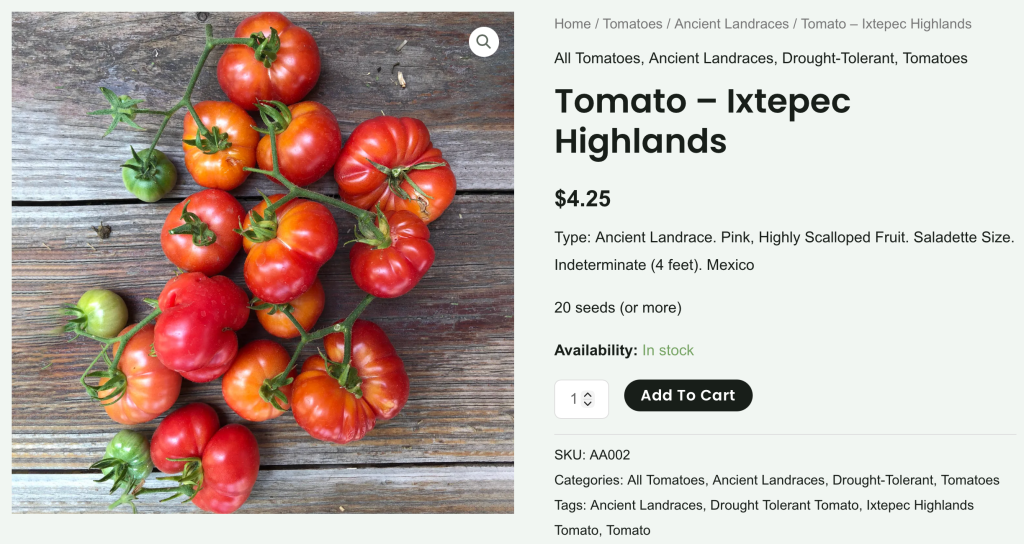

Common Sense Seeds (based in Canada and as of 2025 not selling to the US – we hope someday to order from them) does sell a variety remarkably like our dry-farmed Oaxacan Pink fruit called Ixtepec Highlands, and traced its source: “We chatted with George McLaughlin in Oklahoma, and he was able to tell us that he had collected the seed while living in Mexico in the early 1990s. George was always on the lookout for local, Indigenous tomatoes to save seed from and then share the seeds with the SSE [Seed Savers Exchange].

This variety was collected from a market in the small Zapotec city of Ixtepec, in southern Oaxaca. Zapotec people have been cultivating vegetables in this area for more than 5,000 years.”

(We suspect that the “peach shoulders” on the Ixtepec Highlands variety is actually a mild form of sunscald, to which our own fruit is highly susceptible and which was more prevalent in 2023. In 2025 when utilizing the shade screen, our fruit had a consistently pink-hued deep red.)

Thinking back to Rich Farm Garden’s Oaxacan Pink “revived from a single fruit” we remembered a description of tomato seed saving practices in Oaxaca in a research paper by Jesus B. Estrada-Castellanos et al. :

… traditional methods for obtaining seed. Although there are slight variations among them, the core method can be summarized as follows: “The finest tomatoes are chosen and crushed and squeezed by hand; the seeds and pulp are placed in a ‘sieve’ (homemade screen) where they are sometimes rinsed with water. The seed and pulp waste are then deposited on paper to dry. Once dry and prior to sowing, they are broken down to separate the seed”. As for the movement of seed between and within communities, it was determined that 27% of producers have their own seed, 45% ‘borrow’ seed from a relative and later return the same amount, and 28% get the seed in other communities, in the regional market of Miahuatlan de Porfirio Diaz or in the city of Oaxaca. This local seed supply system is a peasant strategy that promotes conservation of local genetic material (landraces or native varieties) in place of diversification, eliminates the costs that would otherwise be borne by buying seed from distribution companies, and increases the adaptability of landraces to specific agro-ecological micro-niches, as has been documented for maize in Oaxaca (Badstue et al., 2006).

Pondering the actual mechanics by which seeds from landrace populations in Oaxaca end up in the US and Canada: Mr. McLaughlin presumably purchased fruit from a market in Ixtepec from which to save seeds rather than purchasing seeds themselves from a farmer. Those who cultivate and maintain landrace populations understand the importance of maintaining diversity: saving seed from a single or a handful of fruit is likely to be only a narrow snapshot of a landrace population – and may not contain the genes of those plants that will be productive in and adapted to next years’ weather. Likewise, we recall Dr. Michael Kotutwa Johnson emphasizing that seed banks are not functional – seeds must be grown and saved every year to continue to adapt to a variable and changing climate. We would be happy to be incorrect, but we assume that the origin(s) of Oaxacan Pink seeds were not purchased or borrowed in the traditional manner in which a large, variable population of seeds from many fruit and plants would have been sold or shared.

Our Oaxacan Pinks

We suspect that our Oaxacan Pink tomatoes, having been grown on our site for four successive years in the presence of other varieties and abundant native bee populations, are now genetically diverse. How much or how little they have been influenced by the other varieties that we have grown and whether the initial appearance of the Mystery Plum type represented the variety or recessive genetics within a Oaxacan landrace, a hybrid or another variety altogether, we will surely never know. We didn’t deliberately set out to breed unique tomato varieties that are specially adapted to being dry farmed on our site, but that seems to be what we are doing! Our Oaxacan Pink tomatoes are developing a little bit of a following at our market stand, and we plan to continue fine-tuning our growing methods and hope to increase yield over time. We also plan to continue growing and saving Pink Teresa cherry tomatoes and the mysterious Mystery Plum type fruit.

But is it really the lack of irrigation that makes our Oaxacan Pink tomatoes so flavorful? Dry Farming has become synonymous with intense flavor due to California’s success with dry farming the Early Girl tomato variety (a patented hybrid variety now owned by Monsanto), and, frankly, if the flavor isn’t better with dry farming – there’s really little reason to utilize a potentially more difficult and lower yielding growing method. When we try to explain, briefly and intelligibly, how the method of dry farming results in intense flavor at our market stand (that the plants must send their roots deep into the soil during the growing season to search for water and nutrients and in the process encounter more soil and micronutrients than an irrigated tomato plant would, resulting in smaller fruit with less water content but more intense flavor), we often wonder how much bias this creates in the perception of flavor. Bias or not, we are happy to be a part of creating an environment in which people can stop and connect emotionally with their food and with agriculture. But as far as credit for flavor, we believe that a large portion of the credit for our tomatoes’ flavor belongs not to the growing method of dry farming, but to the generations of peoples in Oaxaca who have developed and continue to maintain landrace tomato populations of resilient plants with the finest fruit grown for local markets.

Oaxacan Pink, Mystery Plum, Pink Teresa & Matt’s Wild Cherry